Several decades ago, in search of a new pair of running shoes, I walked into a San Francisco shop so small it was almost possible to reach out and touch the display shoes on each of two long walls at the same time. The signage out front said “athletic shoes,” but most of the samples were for jogging or racing.

The clerk behind the counter was also the owner, and was dressed in running shorts and a t-shirt from a marathon a few years before. While helping me select a pair of shoes, he talked about the power of focus, citing the example of Tiger Woods. Tiger’s father had started him young at golf and kept his attention on the game.

“He’s a prime example of what you can accomplish if you stay singularly committed to one objective,” the owner said, back at the counter and bagging my shoes. As he handed them to me, he grew quiet and his face seemed to cloud over. He was still standing at the counter as I left the store, ruminating on something, a regret perhaps, over having let distractions get in the way of his own pursuit of excellence.

Specialization is the culture in which we swim, more so today than ever. Fifty years ago, school kids rotated through different sports with the seasons. Today they’re encouraged to focus on a single sport year-round to increase their chances of mastery and scholarships. Colleges ask students to declare a major as soon as they apply, rather than explore different interests the first year or two.

Malcolm Gladwell added fuel to the fire a decade ago in his book “Outliers,” which contended that mastering a skill required devoting 10,000 hours to the task. This doesn’t leave time for much else. The alternative is to settle for being merely competent, a jack-of-all trades, or worse, a dilettante.

No wonder so many of us leave behind our varied interests as we move from school into our careers and busy lives. “Adulting” means giving up “childish pastimes” and turning our attention to more important problems and the business of getting on in life.

All this specialization may be counterproductive, though. In a book published last year, “Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World,” David Epstein makes the case that the people best positioned to solve the intractable problems of today and tomorrow are ones who have cultivated a broad set of interests and skills that they can draw upon to develop creative solutions.

He cites the example of scientists. Exploring the frontier of knowledge in biology, chemistry and physics requires decades of intense study. If you do make it through the education, you are rewarded with yet greater challenges of competing for scarce funding, getting published, and persuading skeptical peers that your ideas hold water.

This would seem to be a group that has no time for distractions. Yet as Epstein documents, the most renowned scientists are more likely to have interests outside of work than the average scientist. Nobel Prize winners are “about 25 times more likely to sing, dance or act than the average scientist. They are also 17 times more likely to create visual art, 12 times more likely to write poetry and four times more likely to be a musician.” 1

© Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Albert Einstein is a good example. The poster child for genius in the twentieth century, he had a reputation for being absorbed by his work in theoretical physics to the exclusion of quotidian cares like breakfast, lunch and dinner. But he was also an accomplished violinist, carrying his violin that he called “Lina” with him everywhere he traveled. He enjoyed meeting with local musicians to play in classical ensembles and said that if he hadn’t been a scientist, he would have been a musician.

His avocation, moreover, enhanced his primary work, rather than being a distraction. “Music helps him when he is thinking about his theories,” said his wife Elsa. “He goes to his study, comes back, strikes a few chords on the piano, jots something down, returns to his study.” 2

Einstein is a good example to keep in mind this time of year as many of us pause to ponder our priorities. While time and discipline often seem like the biggest stumbling blocks, the real problem may be something deeper: we’re not convinced that we’ll benefit, particularly if something doesn’t seem likely to advance our core pursuits.

If we haven’t persuaded ourselves that a goal is worthwhile, it doesn’t help to write it down or block out time on the calendar. These are good techniques for achieving goals, but work only once sufficient incentives are in place. For this, we need a sense of the bigger picture and how an activity complements the rest of our life.

In audio engineering, there’s a device known as an “equalizer” that’s used to adjust different sound frequencies to create a desired musical effect. The treble and bass controls in a car stereo are a simple example of this.

Recording engineers and audiophiles use more elaborate equalizers with an array of knobs that divide sound into finer strands. Any one strand might not sound that nice -- e.g., the lowest bass frequency alone will give you audio sludge. But combined in proper proportions to fit the configuration of instruments, characteristics of the room, and listener preferences, they can create beautiful music.

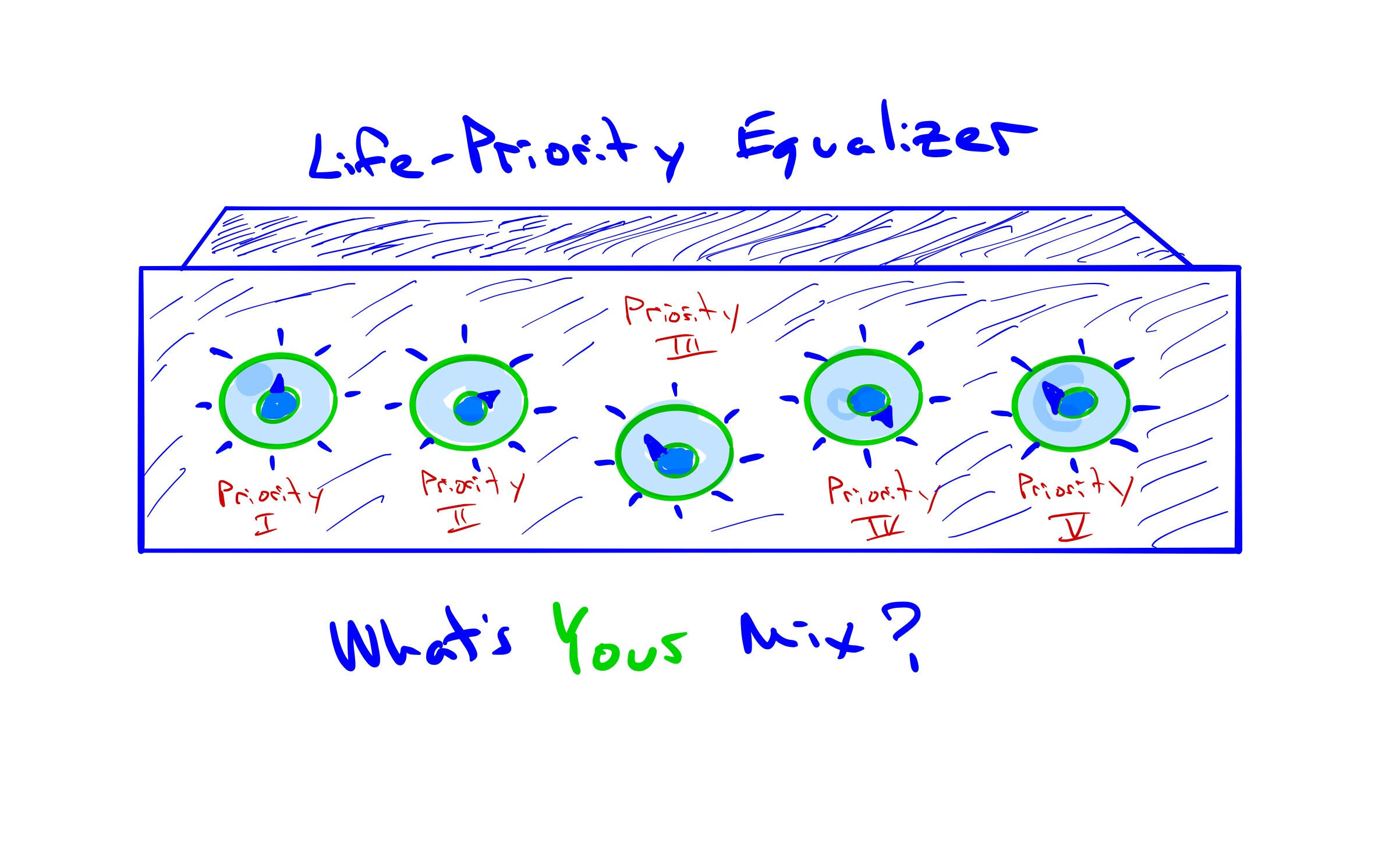

What if we had a “life-priority equalizer” to create a blend of activities into a sum greater than its parts? It might look something like this:

The knobs could represent anything you like -- e.g., individual interests; areas of life such as family, work, exercise and hobbies. The main point of the metaphor is to remind us that while certain goals require more of us, we can still have multiple goals, with varied degrees of commitment. This means we can pursue an interest simply to explore, see the world more clearly, or even just have fun.

Our eagerness to excel often prevents us from accepting this. A former practicing artist who now has a professional career and a family avoids picking up a brush to paint again because she knows how much time it will take to do it well. What if painting a couple of hours every week, even poorly, enhanced her effectiveness in the rest of her life?

With an equalizer, you can adjust your mix of activities to suit the occasion. Starting a new job, the birth of a child, or tending to one’s health may require us to deemphasize some activities for a while. This doesn’t mean they faded into the past; they’re simply turned down for the moment.

Most important, the equalizer invites us to experiment, not just when we’re young, but all our lives. In contrast to one-time events like graduation day or crossing a finish line, creating the perfect mix of activities for ourselves is an ongoing process of discovery. We increase the odds of success by tinkering with the knobs, using trial and error, like we did as children, when work was play and play was work, and we better understood how it all fit together.

1 "Why Some People Are Impossibly Talented", BBC.com, David Robson, November 18, 2019.

2 "Inside Einstein’s Love Affair With ‘Lina’—His Cherished Violin", National Geographic, February 3, 2017.