Mortgage rates have dropped again, and bragging rights are being assigned based on who can secure the best deal on a refinance. One client locked in a 15-year mortgage at 2.5%, another a 30-year loan at 2.875%.

Even during the 2008-2009 financial crisis, when central banks poured billions of dollars into their economies to encourage lending, rates didn’t fall this low. In August 2009, mortgage rates hovered around 5.25%. This was a great deal compared to the 8% mortgages a decade before, but practically usurious compared to today’s rates.

The lower the rate, of course, the less a borrower must pay in interest and thus monthly mortgage payments. Even more impressive is how much money a lower rate can save a borrower over the life of a loan, particularly with the larger mortgages common in high-cost areas such as the SF Bay Area.

As the chart below shows, on an $800,000 loan with a 5.25% rate, a homeowner will pay almost as much interest as the loan principal itself over 30 years. Dropping the rate to 3.25% reduces the lifetime interest by more than 40%, and if you also reduce the loan term from 30 to 15 years, the lifetime interest that you pay drops to about a quarter of the loan balance.

It seems like a no-brainer that borrowers should refinance if they can lower their mortgage rate. But it’s not. Since the 1930’s, most mortgages have been “amortizing loans” that spread out payments on the loan principal and interest over the life of the loan, with each fixed monthly payment containing some of each.

This makes the loan payments more manageable than the earlier practice of requiring the borrower to pay back only interest during the loan term, typically over five to ten years, with a large balloon payment due at the end for the loan principal. But it also means that lowering your loan’s interest rate may not actually save you money.

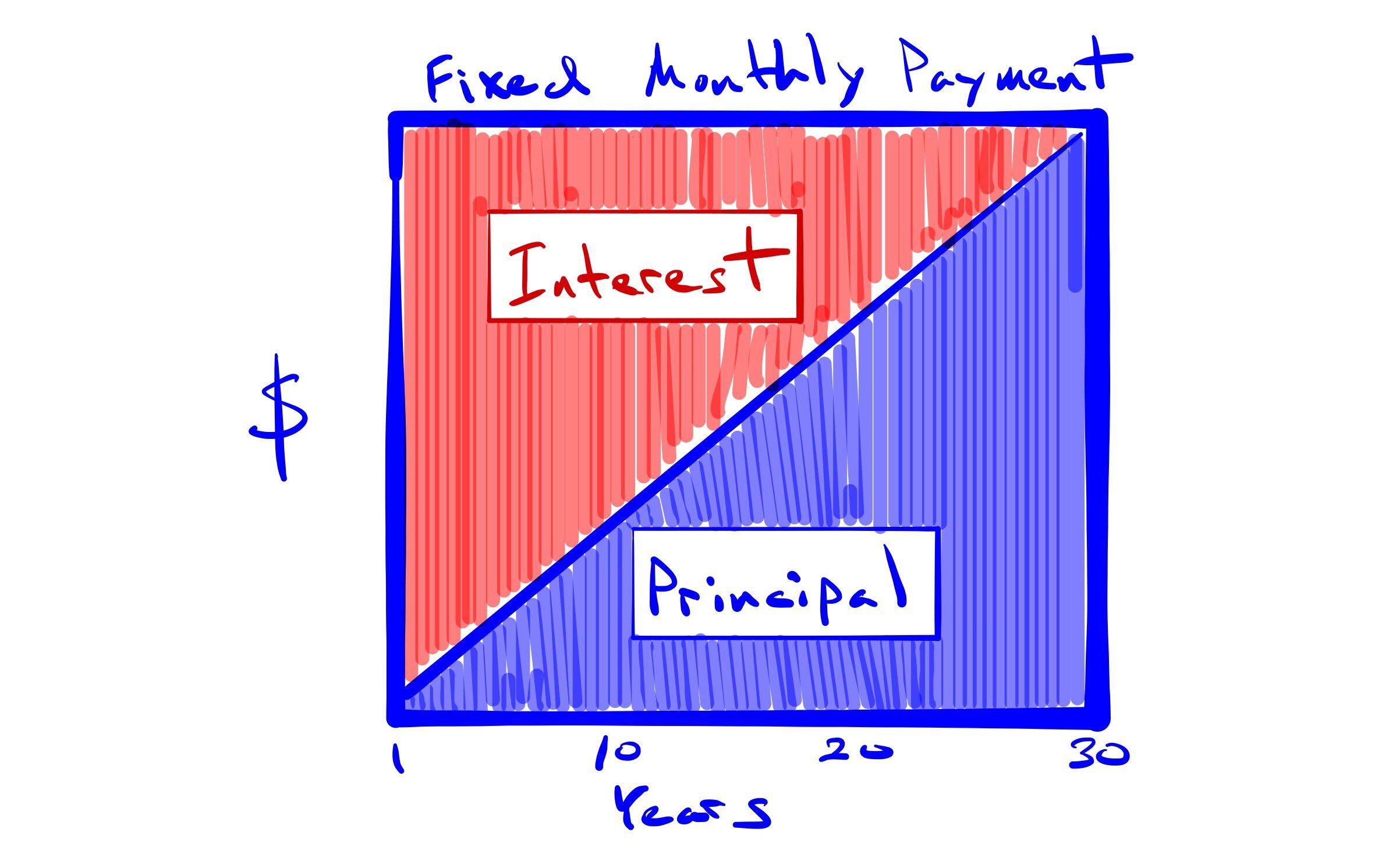

For the vast majority of loans, the fixed monthly payments gradually shift the amount of each payment that is applied to principal and interest as the loan is paid down. During the early years, the monthly payment goes almost entirely to paying the interest. By the end of the loan, the payments go almost entirely to principal. You end up with the pattern in the diagram below of front-loaded interest and back-loaded principal on the fixed monthly payments.

This evolving ratio of principal and interest payments means that borrowers have different opportunities to save money through a refinance, depending on how long they’ve had their loan. (It also means that bragging rights should be based on more than just your mortgage interest rate.)

In the first few years of a loan, with most of the lifetime interest still ahead of you, there may be a large opportunity to save by refinancing to a lower rate. For loans that are nearly paid off, with mostly principal to repay, a refinance may offer no opportunity at all.

To know for sure whether a refinance will save you money, you have to run the numbers, since rules of thumb can be misleading. For example, an old rule said that borrowers needed to be able to lower their rate by at least 2% for a refinance to be worthwhile. This made sense when rates were 8%, but not in today’s world of 3% rates, when dropping your rate by even half a point, or 0.5%, may save you money.

Fortunately, there are numerous online calculators available to help. One of our favorite resources is the Mortgage Professor site, run by Jack M.Guttentag, a Professor of Finance Emeritus at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is another good resource.

What if you can’t save any money with a refinance - are there other reasons to consider one anyway? Well, yes, thank you for asking.

Many people who opted for adjustable-rate mortgages in recent years in order to get the lowest rates available have a great opportunity to refinance and lock in today’s low rates with a fixed-rate mortgage. This eliminates the risk that monthly payments may rise in the future and could make sense even if it means slightly higher monthly payments now.

In addition, a borrower may have other, more productive uses for the equity tied up in their home. For example, the money might help to start a business, fund children’s education, or invest elsewhere at higher expected rates of return.

Here, we enter into territory where mortgage calculators cannot tread. Since a mortgage is but one piece of the larger puzzle of household finances, there are other details to consider such as how long you expect to remain in a home, future job prospects, and your health.

Personal preferences bear heavily on what is the best solution for you. For some people, personal debt of any kind is a weight on their shoulders and may even feel reckless. For others, using mortgage “leverage” to keep money free for other productive uses feels like the smart approach.

All this means that the common refrain in answering most mortgage questions is, “It depends.” What’s best for you, at this moment, will depend on weighing the pros and cons of various options, in the context of your financial situation, and often on making an educated guess about how your life will unfold.

To illustrate, here are some of the questions we’ve been fielding from clients considering a refinance:

Should I decrease my loan term from 30 years to 15 years?

90% of today’s mortgage loans have terms of 30 years for one reason: to minimize the required monthly payments. However, as we saw above, stretching loan payments out longer means paying more interest over the life of the loan.1

Paying more lifetime interest with the 30-year term might make sense if:

- It allows you to accumulate emergency cash reserves or maximize retirement contributions that you couldn’t do otherwise.

- You’re self-employed and experience fluctuating earnings over the course of the year.

- You’re concerned about a potential job loss and the resulting strain on cash flow.

On the other hand, converting your 30-year loan to a 15-year mortgage will commit you to paying off the debt sooner and could save quite a bit of money. The monthly loan payments will be quite a bit higher than the 30-year loan, though, so you need to be sure you can make them.

Fortunately, there’s a middle path for people who have the financial wherewithal and discipline: you can simply make extra voluntary payments with your monthly mortgage payments and instruct the lender to apply it to the loan principal. This can achieve most of the savings of the 15-year loan while maintaining flexibility, should you need it, with the lower payments of the 30-year loan.

This was the case recently for a client. She already had a good rate of 3.375% on a loan with 22 years remaining and a balance of $292,000. She could lower the rate to either 2.875% or 2.35% on two 15-year loans offered by different lenders.

With her current loan, she had $122,000 of interest left to pay. With the 2.875% loan, she would pay $68,000 of interest over 15 years, and with the 2.35% loan, she’d pay $55,000 of interest.

Refinancing seemed like a good idea until we considered:

- She could lower the lifetime interest on her current loan to $81,000 and reduce the term to 15 years by voluntarily paying an extra $500 a month with her mortgage payments (making them comparable to the payments on the 15-year loans).

- There were costs to refinance into the 15-year loans, which reduced their savings, and the lowest-rate loan required her to maintain a large cash balance in a bank account, an opportunity cost that could eliminate any interest savings.

What initially looked like fantastic opportunities to refinance into tantalizingly low rates turned out to be less attractive than what the client could achieve with extra payments, since they helped achieve most of what the new loans offered while maintaining flexibility with her payments should the need arise to pay less.

Should I roll the closing costs into the new loan?

Financial innovation comes with a cost, and it’s amazing how many different service providers are involved in facilitating a mortgage transaction. There are title companies, escrow accounts, underwriters, and mortgage brokers, among others. Individually, they don’t ask for much in fees, but it can add up to a few thousand dollars for the privilege of replacing your current loan with a new one.

Yes, you should make sure you understand these costs and confirm that they’re in line with comparable deals you can find elsewhere. But assuming you’ve done that, our typical advice with closing costs is, Don’t overthink it.

A lot of ink has been spilled over the pro’s and con’s of paying closing costs out of pocket, which often gives you access to a slightly lower interest rate, or rolling them into your new loan at a slightly higher rate. If you know you’ll remain in your house forever, it probably makes sense to pay the costs yourself for the lower rate.

However, the interest-rate differences usually aren’t much different, and if you roll the closing costs into your new loan and later regret the decision, you could simply make some extra voluntary payments on your loan to achieve what you would have done if you’d paid the costs out of pocket.

Should I pay “points” to reduce the mortgage further?

A “point” is a form of prepaid interest, and one point equals 1% of the mortgage loan amount, i.e., $8,000 on an $800,000 mortgage.

Mortgage lenders often offer borrowers the ability to pay a point in exchange for a slightly lower interest rate. Prepaying interest through points may make sense if you know you’ll stay in your house long enough to recoup the benefits from the lower interest rate. Doing a break-even analysis to see how many years you’ll need to stay can help guide your decision.

However, here again, it’s easy to overthink the question, especially since, in our experience, there’s often a significant gap between what clients thought would happen over the next several years and what actually did. Moreover, in today’s low-interest environment, the differences that can be achieved by prepaying interest tend not to be very large.

As an aside, the U.S. is apparently the only country where paying points on a loan is common practice. As this article explains, the system of paying points in a mortgage transaction arose back in the 1980’s when prevailing interest rates were so high that lenders would have run afoul of state usury laws if they’d tried to charge market rates:

[U]ntil the 80s, points didn't exist in the world of low, stable rates. When interest rates grew like Topsy (the prime rate exceeded 20% at one point), mortgage rates bumped up against usury ceilings, which placed an upper limit on loan rates. In a state with a 15% ceiling, lenders couldn't legally make loans at 16%. By charging one or more points, the contract would be legal. Absent points, mortgage money would simply have been unavailable.

Should I tap some of my home equity for other needs?

While most people refinance to lower their monthly payments or reduce the overall interest they’re paying on the loan, some people use a “cash-out refinancing” to free up home equity for other purposes such as a home renovation, starting a business, or funding educational expenses.

You’ll see strong opinions for and against using mortgages to fund other types of spending or investment. In the end, it doesn’t seem to make sense to categorize different uses as good or bad. Instead, if you’re going to use a refinance to increase your mortgage debt, the main questions are whether you can afford the new loan payments and are comfortable with the risks. It helps to have a Plan B in place in case your Plan A doesn’t work out.

One cautionary tale: years ago I met a couple who had refinanced their mortgage several times, as house prices kept rising and rates kept falling, to fund college expenses for their children. This was supposedly a “good” use of cash-out refinancing, since student-loan rates were much higher than their mortgage rates. However, by the time they were ready to retire, the carrying costs to maintain the house (mortgage payments, property taxes, insurance and maintenance expenses) represented such a large impediment that they had to sell the home to make retirement affordable. Moral: even good debt can become bad debt under the right circumstances.

Can I still refinance if I’m retired?

Yes, as long as you can show you have adequate income, good credit, and meet other lending standards, you can still get a mortgage loan even though you’re retired.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), passed in 1974, was amended to prohibit lenders from discriminating based on age, among other factors. As a result, lenders cannot limit access to mortgage products based on life expectancy -- for example, by denying a 75-year-old retiree access to a 30-year mortgage. (If the borrower dies during the loan term, the house can be sold to pay off the loan, or the heirs can pay it off themselves.)

The trick is being able to demonstrate that you have access to enough income to cover the mortgage payments through sources such as Social Security, pensions and annuities, and investment assets. Fannie Mae instructs lenders how to verify regular and continued receipt of the income from different sources, and lenders may impose additional requirements.

One common problem for retirees who have assets and can easily afford mortgage payments is that they draw upon their retirement and other investment accounts sporadically. This means they lack the “regular and continuous” streams of income that they enjoyed before retirement, and lenders have been reluctant to make loans in these circumstances.

There are ways to address this problem - for example, by switching to regular monthly retirement withdrawals before applying for a new loan. However, again, any income strategy should be considered in the context of the bigger financial picture.

Should I shop around for a new mortgage or go with my existing lender?

At any given moment, there will usually be a range of opportunities with mortgage terms, so, yes, it pays to shop around for the best deal.

It’s possible your current lender will give you the best rate, and without the need for a new appraisal, so this is the easiest route to take. But you won’t know that you got the best deal unless you call at least a couple of other lenders. You can also shop for rates online from the comfort of your easy chair.

Independent mortgage brokers with access to multiple lenders can be a great one-stop shop for competing mortgage rates. Experienced brokers can also be particularly useful in helping to craft creative solutions where necessary in order to secure the best rate.

1 As an aside, there’s a disconnect between 30-year mortgages and homeowners who stay in their homes an average of thirteen years these days. If you want to read about the history of the 30-year mortgage, Freddie Mac has a good article. If you want to read why some people believe the 30-year mortgage may not survive much longer, take a look at Rising Seas Threaten an American Institution: The 30-Year Mortgage.