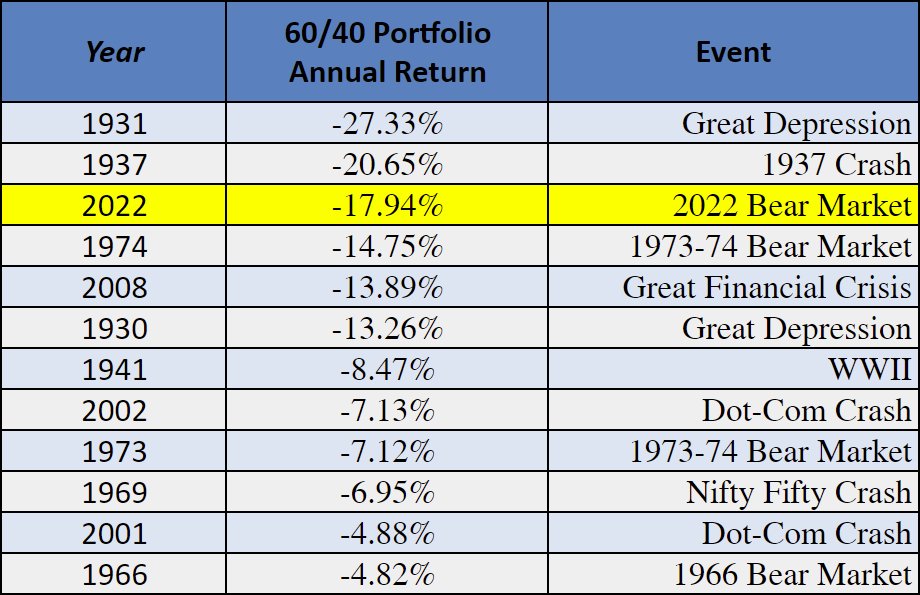

Last year was one of the worst years in the past century for the traditional 60% stock, 40% bond portfolio, worse than during the 2008 credit crisis and nearly as bad as during the Great Depression in the 1930’s. Was this the death knell for traditional asset allocation, and should investors consider something different to protect their financial assets going forward?

To answer this question, we first have to look at what happened last year, and to understand the market declines of 2022, the worst in fifteen years, we need to go back to the beginning of the period. In 2008, the world’s central banks unleashed a policy of zero interest rates in order to shock the global financial system back to life from a near-death credit crisis. The remedy worked but ushered in an historical aberration of rock-bottom rates over the next decade.

After several years of attempting to exit their “quantitative easing” programs, central banks doubled down on them in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic. With factories idled, shipping and transportation frozen, and everyone huddled at home, wondering what would come next, central banks once more raced to the rescue. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve, perhaps emboldened by previous success, poured over $4 trillion into the economy, well over twice what it had done in 2008.

This time there were adverse effects - rampant speculation, consumer and business spending sprees, bloated hiring programs, and the worst inflation in 40 years, which spiked as high as 9.1% last year.

Central banks scrambled to catch up. The Federal Reserve architected a near vertical ascent of its Fed Funds rate, slamming the door shut on previous monetary innovations:

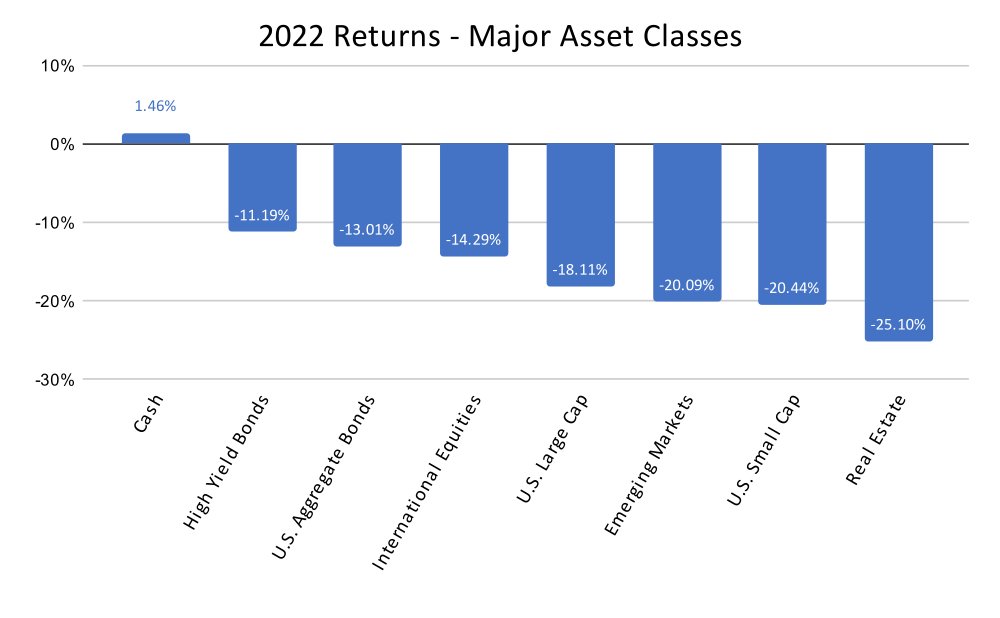

In response, asset values dropped across the board - stocks, real estate, commodities, even gold. Moreover, as the chart below shows, for the first time in half a century, bonds dropped alongside stocks.

Source: Cash: 90-day T-bill; High Yield Bonds: Bloomberg High Yield Bond Index; U.S. Aggregate Bonds: Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index; International Equities: MSCI World ex USA; U.S. Large Cap: S&P 500; Emerging Markets: MSCI Emerging Markets; U.S. Small Cap: Russell 2000; Real Estate: FTSE EPRA Nareit Developed REIT Index

There was life outside the financial markets, but a lot of it wasn’t any cheerier. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, lingering supply chain issues, continued labor shortages, changing work patterns, and questions about what would happen with cities and their commercial districts contributed to growing unease about the future.

Even JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, a beacon of calm during the 2008 financial crisis, succumbed to the dark mood, warning in June of a coming economic “hurricane.” (He recently backed off of these comments, saying last week, “I shouldn’t have ever used the word 'hurricane.'”)

It was in this environment that investors began asking a question that financial analysts have debated for years: is the traditional 60/40 stock-bond portfolio dead?

Many investors view a portfolio allocation of 60% stocks and 40% bonds as a healthy balance between risky stocks and safer bonds, one oriented towards growth while protecting the downside. How healthy can it be, however, when stocks fall and bonds don’t cushion the declines? Investors who hadn’t experienced the varied surprises of the 2000 dot-com bust or the 2008 financial crisis, and who saw stocks rebound magnificently in 2020 were particularly eager to know.

One answer is that bonds have never offered complete protection against stock declines and yet the 60/40 portfolio has still thrived over time. There were only two calendar years before 2022 when both stocks and bonds declined – 1931 and 1969 – but this has happened more often on a quarterly basis, about ten percent of the time since 1926. Often enough, at a minimum, to be expected periodically, particularly during turbulent economic times like the last couple of years.

Another answer is this: it depends on what’s in the “60” and the “40.” In a world of more than 40,000 publicly traded companies and many, many more bonds, one investor’s portfolio can look very different from another even if they both contain, in the aggregate, 60% stocks and 40% bonds.

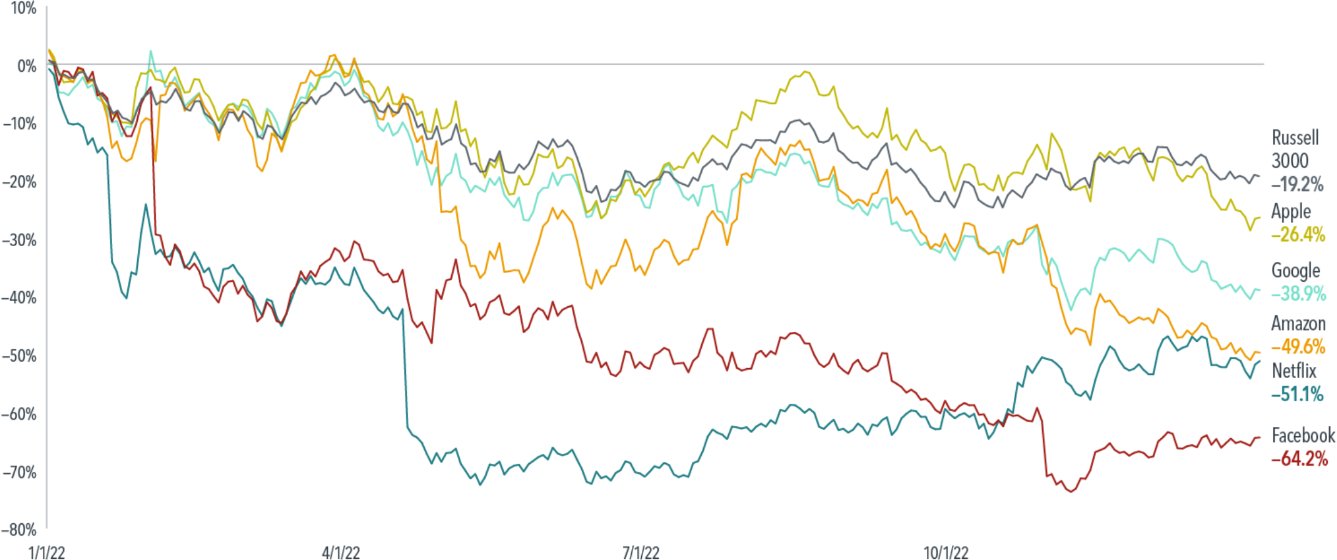

During the last 15 years – as before the dot-com crash in 2000 - investors gravitated towards “growth” stocks, fast-growing companies such as Apple, Google, and Facebook, whose dazzling ideas and market dominance were expected to produce more and more income going forward. Historically, this widespread investor attention has fueled substantial price increases until one day the music stops, perhaps because of a quarterly earnings disappointment or, as last year, because of the rapid interest rate hikes.

These rapid price increases mean that growth companies come to dominate popular stock indices such as the S&P 500 Index and the Russell 3000 Index. This leaves investors who thought they were well-diversified exposed to declines when growth stocks disappoint and their prices fall, bringing the stock indices down with them, as they did last year:

Tech Giants De-FAANGed

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

It was the traditional 60/40 investment portfolios dominated by growth stocks that had the worst experience last year. Examples include the Vanguard Balanced Index Fund, which declined nearly 17%, and the Vanguard STAR Fund, which fell nearly 18%.

To put these returns in perspective, here are the worst years for a 60/40 portfolio comprised of 60% in the S&P 500 and 40% in 10-Year Treasuries since 1928:

Source: NYU Data via Ben Carlson

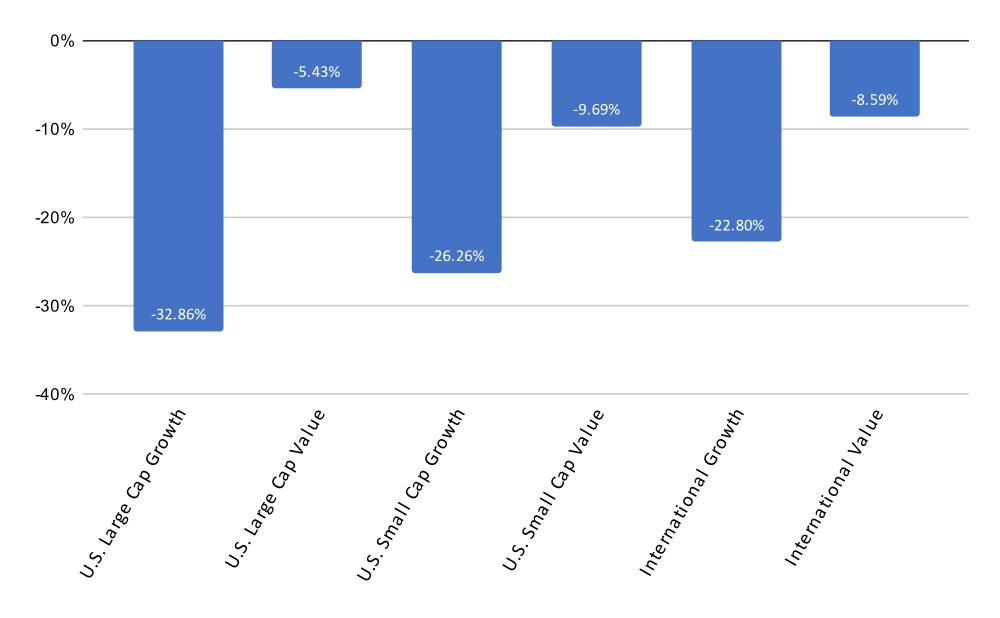

By contrast, investors who diversified beyond growth into value stocks had a much better experience. While value stocks did not escape market declines, they outperformed growth stocks by the largest margin since 2000 during the dot-com bust. For example, the MSCI World Growth Index fell a whopping 29%, whereas the MSCI World Value Index declined about a fifth of that, 5.8%.

The outperformance of value over growth occurred within different market segments as well:

Source: MSCI USA Large Cap Growth Index, MSCI USA Large Cap Value Index, MSCI US Small Cap Value Index, MSCI USA Small Cap Value Index, MSCI ACWI ex USA Growth Index, MSCI ACWI ex USA Value Index.

The irony of value stocks’ relative outperformance last year is that in the years leading up to 2022, one of the most popular investment questions among professional investors was whether “value is dead?” This wasn’t surprising, since value stocks have recently had some of their worst years on record. A lot of investors jettisoned their allocations to value stocks, influenced by recent performance, so presumably missed last year’s turnaround.

Just as California rain will likely never eliminate the possibility of drought, there will always be questions about whether investment strategies can perform well going forward. These questions are inherent in all strategies, given the uncertain future. The essence of sound investing is adopting a strategy that can still be executed with discipline when uncertainty is most evident.

Figuring out the appropriate strategy cannot be done in a vacuum, based solely on investment outlooks, asset valuations, and economic forecasts. For individual investors, it requires an examination of their particular circumstances – financial goals, spending needs, and other details. Investment time horizons matter; so do individual risk preferences and one’s capacity for withstanding investment uncertainty.

Today, the uncertainty is as evident as ever, and 2023 poses a host of questions – will the Fed overshoot with its rate increases, causing further market disruption? What will happen with the latest U.S. debt-ceiling fight? How many more employees will the tech sector shed? How will the war in the Ukraine progress?

The economy and markets may get worse before getting better, further challenging investors to stick with their plans, particularly those who have only invested during the halcyon years since 2008. The investors who succeed will be the ones who remember that in the past, after the markets have shuddered, the returns have followed; and that the search for the perfect plan - perfect protection, perfect returns - is often the biggest threat to a good one.