2021 marked the third year in a row of positive returns in most developed stock markets. For U.S. stocks, it was one of the best years on record and continued a remarkable run that few, if any, people expected after the 2008 financial meltdown. Stocks are volatile now, though, so people are asking, Is it still safe to invest?

If what goes up must come down, last year might not bode well. Here are the 2021 returns for the major asset classes:

Stock valuations are a concern, too. There are always complaints as markets are rising that “stocks are expensive,” but it’s hard to ignore that some types of stocks such as the large growth stocks in the S&P 500 Index – dominated by companies such as Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Amazon and Tesla – are valued as high today by some measures as they were before the dot-com bust twenty-two ago.

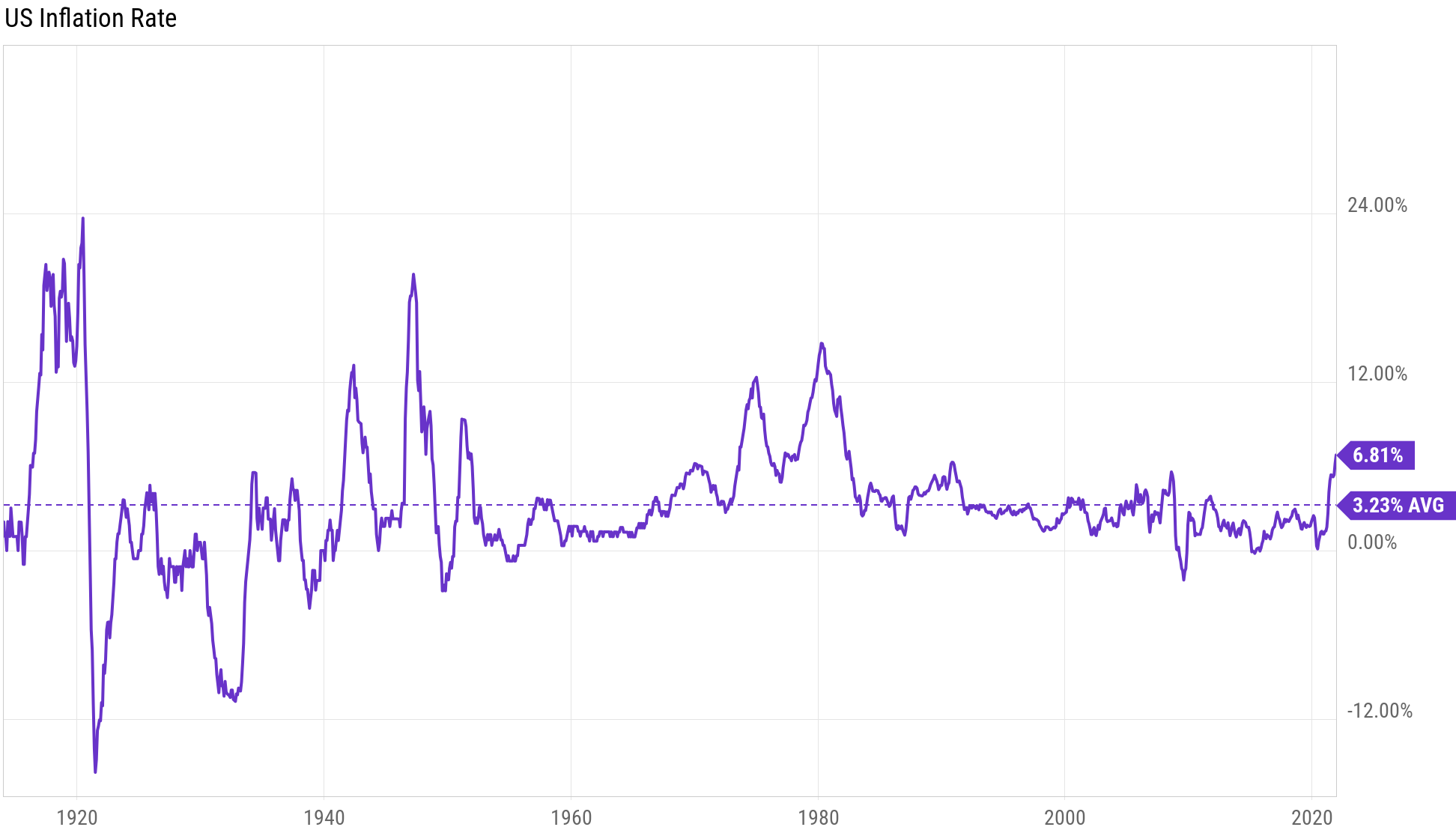

Then there’s inflation. Last year’s inflation spike of nearly 7% was higher than any we’ve seen since the 1980’s:

We expected some year-over-year inflation in 2021, since governments had shut down the global economy the year before. Still, the magnitude of the spike was a bit of a shock, and the Federal Reserve eventually began signaling that it would likely cease its bond-buying program and raise interest rates to try to curb inflation.

The biggest warning sign, though, that stock prices might be getting ahead of themselves was an increased willingness among both institutions and individuals to assume more investment risk. Good times encourage investors to drop their guard, and low interest rates have driven many of them into riskier bets searching for higher returns. However, there seem to be other forces at work that are helping to ramp up risk appetites.

During the “roaring twenties,” shoeshine boys and taxi drivers famously gave their customers stock tips, fueling a retail-investor frenzy that culminated in the 1929 crash. In the 1990’s, day-trading was fueled by internet access to brokerage platforms and the Yahoo! discussion boards before the dot-com bust in 2000.

All that seems like a warm-up for the situation we have today where retail investors receive stock tips from nearly every social media app on their phones. Many people look to Reddit, Facebook, or even TikTok for investment advice. People post their statements on Instagram to show their windfalls from “meme stocks” and share tips that other people implement immediately with a tap and swipe on their Robinhood trading app.

One “meme stock,” video-game retailer GameStop, jumped overnight from the dustbin of small value companies to become a $24 billion company, making it larger than over 200 constituents of the S&P 500 Index and as large as Whirlpool and American Airlines combined.

“Pandemic stocks” such as Zoom and Docusign were also volatile as institutional investors implemented “macro bets” based on their best guesses for where the pandemic would go next. Docusign went from market darling to a distressed asset, soaring from $75 a share in early 2020 to a peak of $315 in mid-2021, only to plunge to $116 recently.

This stock speculation plus widespread investor interest in risky assets such as cryptocurrencies and financing vehicles such as SPAC’s (special purpose acquisition companies) suggest to many observers that it’s possible we’re in the midst of another asset-pricing bubble. If so, at some point, the risk will show up, the music will stop, and the investment world will be filled with disappointment or worse as it has been many times before.

Given all that, what, if anything, should investors be doing now?

The temptation is to try to peer into the future (while telling ourselves that we can’t) and make a forecast to guide our investment decisions. The trouble is, we tend to extrapolate too heavily from whatever is happening around us and to expect the future to look much like the present. This is why market forecasts were so erroneously bleak after the 2008 crisis.

The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.

– Henri-Louis Bergson

It’s also why in May 2020, soon after the government shutdowns and stock-market crash, famed economist Kenneth Rogoff compared the situation to the Great Depression and said, “I don’t know how we’re coming back to 2019 levels [in the economy] in any near term.” When pressed, Rogoff predicted the process might take five years. Instead, it took about a year and a half, and by September 2021, U.S. GDP was back to its pre-pandemic levels.

During uncertain times, we’re also prone to catastrophize and draw unhelpful parallels from past traumas. Ever since the Great Depression in the 1930's, for example, it seems to many people that every major economic recession portends a Great Depression 2.0.

In Nate Silver’s book, “The Signal and the Noise - Why So Many Predictions Fail, But Some Don’t,” which was published in 2012, a time of great interest in predictions after the financial surprises of 2008, he describes a number of predictions that went awry because of our behavioral tendencies and lack of data. The story of the 1976 swine-flu scare in the U.S. packs more of a punch today than it did when the book was published.

As Silver tells it, when a young soldier died from the flu at Fort Dix in New Jersey, the CDC discovered that the virus was not a new strain, but “a ghost from epidemics past: influenza virus type H1N1, more commonly known as the swine flu.” This was the virus that had caused the Spanish flu of 1918-20, which had also first appeared in the U.S. at a military base before World War I. (p. 205)

The parallels between the 1918 and 1976 virus situations “sent a chill through the nation’s epidemiological community.” There was “a belief at the time - based on somewhat flimsy scientific evidence - that a major flu epidemic manifested itself roughly once every ten years.” Since there had been severe outbreaks in 1938, 1947, 1957, and 1968, “in 1976, the world seemed due for the next major pandemic.” Dire predictions followed.

President Gerald Ford authorized a rushed vaccine-development initiative and the first mass-vaccination program since the polio vaccine in the 1950’s. Despite evidence that the H1N1 virus was not as virulent as feared, “frightening public service announcements . . . ran in regular rotation on the nation’s television screens” that “mocked the naivete of those who refused flu shots.”

In the end, the soldier’s death at Ft. Dix turned out to be the only confirmed swine-flu case anywhere in the U.S. There were, however, growing reports of vaccinated people suffering the rare neurological condition known as Guillain-Barre syndrome. Americans became resistant to the idea of getting vaccinated, and over the next couple of years, only about a million of them were willing to get a flu shot, which left the population more exposed than before to a severe flu outbreak.

If our predictions are thrown off course by our behavioral tendencies, what can investors do to protect themselves from an uncertain future?

For starters, they can diversify. There is more than one market, even in the U.S., and many of the approximately 4,000 companies here and some 16,000 companies abroad sit at very different price levels than the large tech stocks in the S&P 500 Index. Diversifying into other areas of the market such as value stocks, both large and small; international and developed stocks; and, of course, bonds, is a risk-management strategy that acknowledges we don’t know what comes next.

It’s an approach, moreover, that historically has helped investors achieve similar returns to the market itself, with less volatility, resulting in better risk-adjusted returns. (See Which Stocks to Pick?)

As we tell clients, the goal is to build a portfolio that can serve as a “container ship” to travel across an ocean of time to achieve your financial goals. This means a portfolio that can perform reasonably well under a variety of economic conditions, rather than one optimized to outperform under a narrow set of conditions (a “speedboat”), since conditions can change quickly and we can’t predict what comes next.

Ideally, you’ve chosen your investment strategy after taking into account all your financial circumstances in a financial plan that helps assess how much capacity for financial risk you have and how much risk you need to take in order to achieve your goals. Long before the market storms arrive, you’ve figured out how much cash to hold in reserve and how you might adapt financially if the markets aren’t as favorable as you hope.

As we’ve written about before (How to Plan for a Future We Can’t Predict - Part II), this type of approach is the essence of good strategic planning, which ultimately directs our attention to the things we can control (reinforcing the house) in preparation for dealing with the things we can’t (the earthquake).

Once you’ve chosen your strategy, the next task is to stick with it. This can mean making emotionally challenging decisions such as rebalancing your portfolio by selling assets that have performed well to purchase those that haven’t in order to stay on target with your investment plan. It can also mean forcing yourself to turn off the news for a spell in order to avoid the undue influence of all the noise that accompanies any market volatility.

What you want to avoid above all else is continually trying to adjust your investment approach in order to “play it safe,” particularly by decreasing your stock allocation each time economic storm clouds appear on the horizon. This is the one thing we know is pretty much guaranteed to erode portfolio returns, as evidenced by the graveyard of mutual-fund managers and other institutional investors who thought they could avoid the storm.

In the long run, trying to play it safe by guessing what may be around the corner and changing course in response is one of the riskiest moves we can make. As Nate Silver put it, “If you can’t make a good prediction, it is very often harmful to pretend that you can.”