In the 1940’s, as the United States entered World World II, forest-fire prevention became a national security concern, particularly in California, where the dry forests were at risk of bombardment by sea. With most firefighters deployed abroad, the Forest Service needed a way to enlist help from a general public long accustomed to fires being somebody else’s responsibility.

Keith Michael Taylor / Shutterstock.com

Smokey Bear was born. His first words were an uninspiring “Care will prevent 9 out of 10 fires.” Then, catching on to how humans really operate, he adopted the slogan that he would use for the next five decades: “Only YOU Can Prevent Forest Fires!”

Smokey Bear’s success begat other public-service mascots to bring voice and personality to otherwise abstract messages in order to harness individual action for collective good. Woodsy Owl (“Give a Hoot, Don’t Pollute”) flew into the picture in 1971. A decade later, McGruff the Crime Dog (“Take a bite out of crime”) arrived on the scene.

No one knows more about the importance of personalizing and simplifying abstract concepts than Wall Street. In contrast to tangible products such as automobiles, computers, and airplanes, what Wall Street sells are ideas. Many of the ideas concern not today, but the future, the realm of imagination, since it’s anybody’s guess what will actually happen tomorrow.

To sell an idea, Wall Street knows, there’s nothing better than a good story, particularly one that allows us to establish a connection with our own lives and provokes us to action. Many of the narratives emanating from Wall Street center on the transformative power of new technologies -- railroads in the 19th century, space technology in the 1960’s, the Internet in the 1990’s, and, more recently, cryptocurrency. Other stories revolve around the mystique of an entrepreneur or investment manager; the inexorable economic forces at work in the world; or the demographic destinies of nations.

A good story doesn’t necessarily make for a good investment, though. As computers came online in the 1960’s and 70’s and investment data was assembled and studied, economists in academia uncovered a story that Wall Street would have preferred to bury in the basement: very few investors, both institutional and individual, were managing to beat the market with their active-trading strategies.

This information spread by word of mouth, gathering speed through the 1980’s and 1990’s, with the rise of index funds and similar market-based investment strategies, altering the investment landscape. As the Financial Times noted:

Index funds have revolutionised investing, saving millions of people untold billions of dollars in fees that would otherwise have gone to fund managers with a dismal long-term record of actually beating the market. It is no exaggeration to say that the rise of passive investing is probably one of the most consequential financial inventions of the past half-century. It is rewiring markets and reshaping the finance industry.1

To try to stem the tide, Wall Street purveyed a number of myths about index funds, chiefly, that they were okay to use in rising markets, when times were good, but you needed an active manager “with their hand on the wheel” to protect yourself during the bad times. The 2008 global financial crisis blew this myth out of the water, and passive investing took off like wildfire.

Wall Street was right, though, about investors’ need for a good story to help them stay the course. We’re biologically wired to seek patterns in order to make sense out of uncertainty, and stories help us do this.

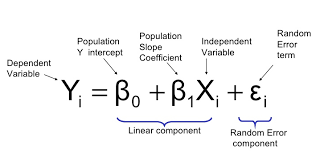

Which presents a problem for market-based funds, built not on tall tales, but on wonky academic formulas like this:

While markets are rising, it’s all well and good to say that the investment products were designed by respectable academic scientists in white lab coats. When the waters get rough, investors want something better than science. They want a reason to believe that they’ll be safe.

When there’s simply data, it’s all noise. It’s impossible for a human being to absorb data without a narrative.

- Seth Godin

The problem is, there’s no investment product in the world that can supply that story. For that, we have to look at something which, on its face, during a moment of crisis, seems utterly inadequate: our investment process.

To emphasize this point, David Swensen, the famed manager of the Yale Endowment, tells a story from the 1980’s, when the bottom fell out of the markets. On Black Monday, October 19, 1987, stocks around the world suddenly dropped twenty percent. The next day, Mr. Swensen rebalanced the Yale portfolio, per its investment policies, bringing it back in line with the allocation targets.

The Yale Investment Committee had a fit and called an emergency meeting. Though they had just reaffirmed the university's investment policies a few months earlier, committee members now criticized Mr. Swensen. One member called the previously approved asset allocation "on the far edge of aggressiveness," citing the "bleak short-term prospects for equities," and argued that the stocks should be reduced. Another questioned whether stocks made sense at all anymore.

As Mr. Swensen saw it, the committee members' fear nearly sank the investment discipline just when the endowment needed it most by “exposing Yale to the risk of an untimely reversal of strategy.” Fortunately, he prevailed and was able to keep Yale invested for the enormous market rebound the next day -- in a pattern we’ve seen many times since, with the best market days often following closely on the heels of the worst ones.

Reflecting on this experience, Mr. Swensen noted:

In many ways, establishing policy asset allocation targets represents the heart of the investment process. No other aspect of portfolio management plays as great a role in determining a fund's ultimate performance, and no other statement says as much about the character of a fund. . . . Without a disciplined, rigorous process for setting asset allocation targets, effective portfolio management becomes impossible.2

A sound investment process creates a presumption in favor of your existing strategy. This doesn’t mean that you turn off your thinking cap. It means you should think twice before changing anything, since doing so exposes the portfolio to other risks.

The investor’s chief problem — and even his worst enemy — is likely to be himself.

- Benjamin Graham

When investors refuse to follow their predetermined strategy, they often justify it by saying that they’re only “putting it on pause” until “the market volatility has time to play out.” Isn’t it prudent to pull the car to the side of the road during a heavy rainstorm?

The reality is, in “pausing” the old plan, they’re replacing it with a new one. Whether deciding not to rebalance, shift assets to new managers, or hit the eject button altogether, they’re altering course and now headed in a different direction. Where the previous plan was a considered assessment of risk and objectives, the new one amounts to no more than “Jump!” You’ll figure out where to swim afterwards.

It doesn’t take much reflection to know that adopting a new plan under duress is probably not the best way to tilt the odds in your favor.

1 Passive Attack: The Story of a Wall Street Revolution,” Financial Times, December 19, 2018.

2 Pioneering Investment Management, David F. Swensen (The Free Press 2000), p. 329.