Is it really more difficult to learn new things as we grow older, or is it just that we stop trying? This was my question as I drove home from the first day of a one-week drawing workshop the summer before last. My head felt as if I’d been doing math problems all day, and I was a little stunned by how strenuous the class had been.

The workshop, “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain,” was based on a 1979 book by Betty Edwards, a high school and college art teacher. New research showing that the two hemispheres of the brain were responsible for different functions supported her own experience with students’ drawing difficulties. She had developed exercises to help the visually oriented right brain quiet the left brain’s dominant language skills so that students could draw.

Betty believed that drawing should not be left to artists, especially since artists themselves had abandoned drawing in favor of twentieth-century movements like abstract impressionism. A whole generation of art students had graduated without learning even the basics, and many of them, now art teachers, came to Betty’s courses for remedial learning.

Instead, as Betty taught, drawing was a basic life skill that anyone could learn and had long been taught alongside reading, writing and arithmetic. Scientists like Charles Darwin drew in order to document their discoveries. Thomas Jefferson worked out his ideas for the new Capitol building in a sketch. Photography had given us amazing visual technology, but had robbed us of the problem-solving benefits of drawing along with its aesthetic pleasures.

Betty’s son Brian Bomeisler greeted students as we walked into a fluorescent-lit conference room at the DoubleTree Hotel in Berkeley. A large man with gray hair, Buddy-Holly glasses, black t-shirt and jeans, he was a talented New York artist who had helped Betty develop the course and had taught it around the world for years.

There were nine students, split between men and women in their thirties to late sixties, who had worked or were working in software development, mechanical engineering, physical therapy, medicine, law, and stage design. A few had taken art classes before, and a couple had tried to get through Betty’s book on their own, but drawing was still a mystery to all of us.

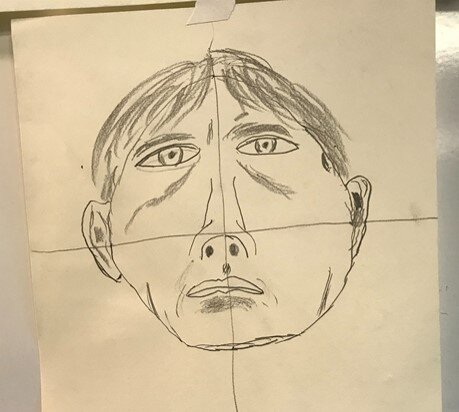

Brian delivered an introduction and pep talk, then gave us our first assignment, a “pre-instruction self-portrait” using the small mirror and other tools from the plastic portfolio we’d grabbed on the way to our seats. We had twenty minutes to work, and when time was up, here’s what I’d produced:

The snout and eyes amuse me every time, but I was relieved to have anything to show. Those twenty minutes staring at my reflection, trying to figure out where to start and how to approximate what I was seeing were some of the most confusing, anxious moments I’ve experienced.

Brian said the portrait revealed the age at which we had stopped drawing. Most of us, it seemed, had put away our drawing pencils and crayons somewhere between the ages of eight and ten, well before adolescence. By Friday, he said, we would have learned enough to do a realistic self-portrait. As the class began to chuckle at the idea, he said, “I’ve helped thousands of students and never had anyone who didn’t arrive at the destination.”

Concerns about the final self-portrait hung over us all week. At lunch and between drawing sessions, we’d joke that we were going to be Brian’s Waterloo. While the camaraderie was nice, it also made me feel worse, since it was hard to see how this wouldn’t be the case with me.

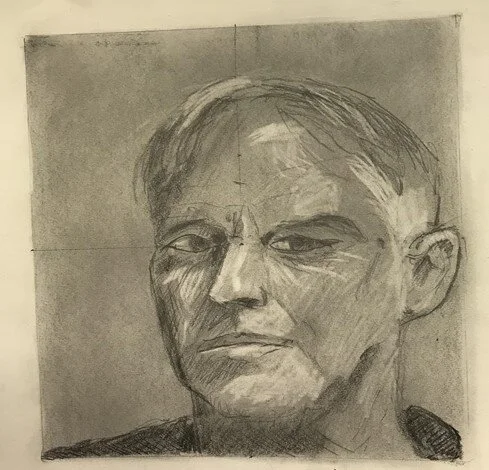

Yet Brian’s prediction proved accurate, and on Friday, thanks to his instruction, here’s what I produced:

When I showed this off to my son, he said, “But you got help, right?”

Yes, Brian provided suggestions as we drew, just as he had all week, to help correct our “misperceptions.” We also had half a morning and an entire afternoon, rather than twenty minutes, to do the final drawing.

Most of all, though, we had new skills acquired through forty hours of lecture and practice - the equivalent, Brian pointed out, of a college semester. Betty Edwards was right: anyone could learn the basics of how to draw if they were willing to invest the time and effort.

Acquiring these skills, though, had required fortitude; the workshop wasn’t so much a class as “drawing bootcamp.”

On the second day, as I struggled for hours to capture the “negative space” required to render a three-dimensional chair, I came within inches of throwing down my pencil and leaving the room in tears as Brian said the French ambassador’s wife had done in Japan. Even after I finished, I thought about not coming back the next day.

As children, we went through similar challenges every week. We moved from class to class, solving problems, taking tests and enduring sometimes overwhelming feelings of incompetence on our way to becoming proficient in the skills required to take care of ourselves as adults.

Before formal education, we made even more herculean efforts to learn how to walk and talk. There was a study years ago where American football players were asked to follow two-year-olds through their day, copying their movements. After a few hours, the athletes were exhausted, which is not a surprise, given that toddlers expend as much energy during the day as an adult running a marathon.

As toddlers grow, though, their pace slows until most become sedentary adults, and it’s the same with learning new skills. Somewhere along the way we plateau. When was the last time you got better at driving your car? After the driving test, we spend decades on autopilot, daydreaming through one errand and commute after another.

It’s easy to see how years later, if we do decide to learn something new, for work or a hobby, we find the task difficult. Having cruised along in our routines for decades, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Yet many of us experience the frustrations that accompany education as a shock. We’re then prone to blame our difficulties on the inexorable declines of aging rather than something less deterministic: we’ve fallen out of practice.

This isn’t to minimize the biological causes of cognitive decline for which there is ample evidence. Evidently even our brain circuitry causes many of us to lose our motivation to learn.

However, there’s also evidence that we abet these biological processes through our inactivity. One study of memory loss among older adults found that it had occurred exclusively in those who had retired, suggesting that “a risk to retiring is that it can speed up the aging of our brain.”

Learning new skills can counter this effect, helping facilitate brain “plasticity” to keep it younger and nimbler and even stave off dementia. This was the motivation for a couple of the older students to enroll in the drawing workshop.

The situation is likely different for each of us, but even if learning does become more difficult as we age, it probably pays to pretend otherwise. Otherwise, believing we’re too old to learn, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

After the course, I bought a sketchbook and continued to draw. There is still the anxiety of making the first marks, but Brian’s encouragement helps me get started. “Put one foot in front of the other and the drawing starts to emerge.” “If you make a misperception with the pen, you just turn the page.”

At work, we’re developing our visual communication skills, and last spring hosted a client webinar with best-selling author and visual communicator Dan Roam, who taught us about the power of combining pictures with words.

Learning begets learning, but, yes, it’s a pain in the butt, and I like to joke that I “wouldn’t wish growth on anyone.” The opposite of growth is worse, though, and I hope as I age that I’ll continue to strive to learn and endure the necessary frustration, keeping in mind the exhortations of the poet Dylan Thomas to his dying father:

Do not go gentle into that good night

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.