People move to California for the climate, the mountains, and the sea, not for the earthquakes. There are about fifty quakes a day around the state, but the big ones are far enough apart that they always come as a surprise.

Each one is different, too, so it’s hard to anticipate what kind of destruction it will bring. The 1994 Northridge quake, for example, happened on an undocumented fault line in the San Fernando Valley and cracked metal welds that were supposed to protect high-rise buildings. Parts of Santa Monica were hit harder than places near the epicenter fourteen miles away, causing seismologists to question what they knew about soil composition and how seismic waves travel underground.

The 2008 global financial crisis upended similar assumptions about the capital markets. Since then, it’s taken fortitude for investors not to run for cover each time the markets shake. Now, with rumors of recession swirling, even investors who stayed the course are asking whether there’s anything they can do to protect their portfolios from the next downturn.

A recent research paper, “The Best Strategies for the Worst of Times: Can Portfolios Be Crisis Proofed?” looked at this question. The authors foreshadowed their findings by noting that “hedging equity portfolios is notoriously difficult and expensive.” They then evaluated how several strategies for hedging the S&P 500 Index had worked over the past three and a half decades, through market upswings and downturns from 1987 through 2018. Their answer: “Possibly yes, but at very high cost.”

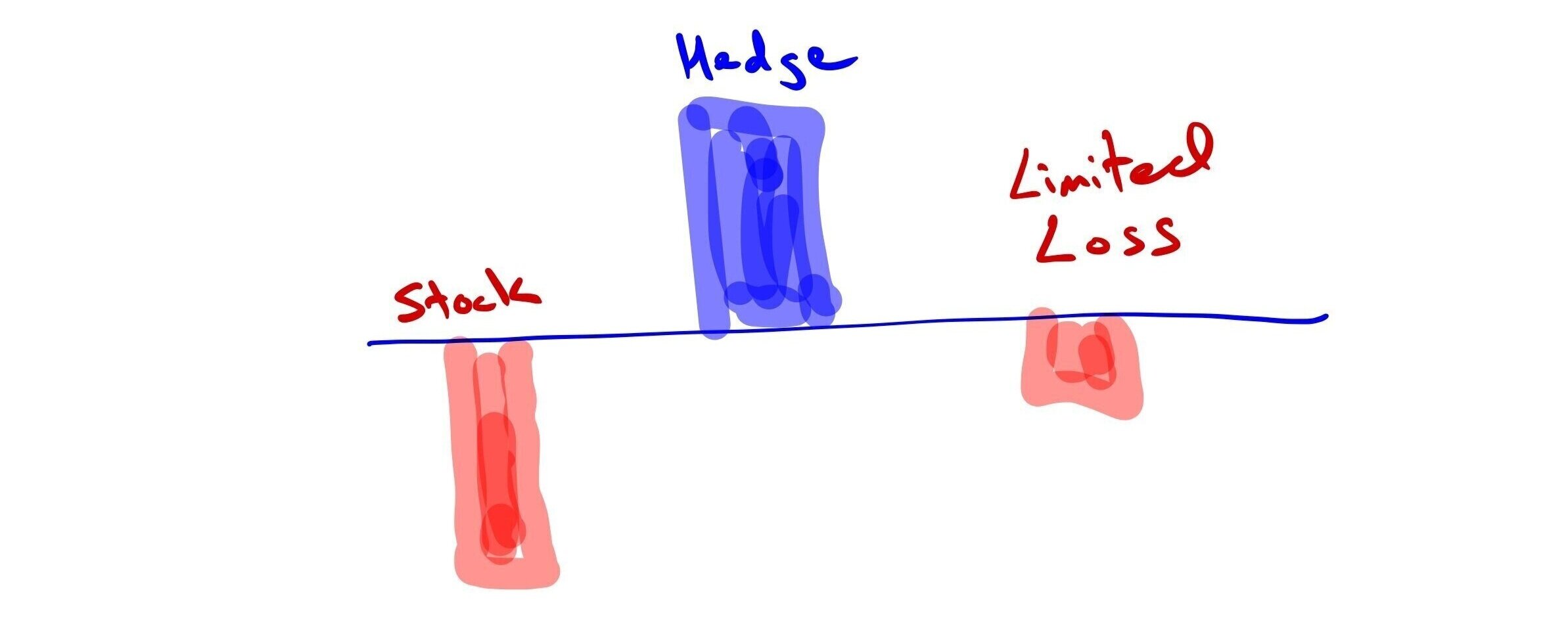

Hedging your bets is one of the oldest strategies in the book. If you don’t know which horse will win, you bet on several to limit your potential loss. With a stock portfolio, you buy assets that are expected to rise when stocks fall.

You could, of course, simply sell your stocks before an expected downturn and avoid declines altogether. But you might be wrong, so run the risk of missing out on significant gains.

Hedging offers the possibility of a middle path, and a lot of financial-product purveyors cater to this hope with flowery promises of “uncapped participation” in market gains with “buffered protection.” But it’s an elusive goal, as the research study showed, for several reasons.

Out-of-Pocket Costs

Most hedges cost money to purchase, which eats into investment gains. The best hedges come with the highest price tags, and prices surge like car-share rides during rush hour when markets become volatile and you most want protection.

For example, put options - the right to sell your stocks at high prices should the market fall in the future. They’re the most direct hedge for stocks, but the study found that hedging the S&P 500 Index with puts over the past three and half decades subtracted a whopping 7.4% from the Index’s returns per year.

That could be enough to devour all of a portfolio’s gains, and it didn’t include transaction costs, which would have subtracted even more. There are ways to reduce the cost of puts, but as the authors noted, these can dilute the value of the hedge and raise questions about its reliability.

Opportunity Costs

A hedge can be wonderful protection during a severe market downturn, but most of the time the stock market isn’t in one. The study’s authors defined a severe downturn as a decline of greater than 15% from the S&P 500 Index’s recent peak. There were eight such declines since 1987, including one last year. But during 86% of the market days over three and a half decades, the market experienced its normal ups and downs as stock prices continued to rise over time during one of the longest bull runs on record.

That’s a lot of opportunity to give up to a hedge even if it doesn’t cost a lot to purchase. This is the story with gold, one of the oldest hedges in times of trouble. Gold worked well as a hedge during all the severe downturns in the last thirty-four years, but had negative returns during normal times, so was flat over the entire period and weighed heavily on stocks.

Plus, the authors noted there is evidence to suggest that “gold is an unreliable crisis hedge and an unreliable unexpected inflation hedge.” Which brings up the next point.

Might Not Work

After the Northridge quake, there was a story about a homeowner near the epicenter who had prepared for the next big one by filling his camper full of water, food, and other supplies. However, he parked the camper in his driveway, and when the gas line on his property ruptured, an explosion took down both his house and the camper in one swoop.

A lot of attempted stock hedges have blown up in similarly dramatic fashion as we saw with things like credit swaps during the financial crisis a decade ago. Thus, while the study’s authors did identify two trading strategies that served as good hedges during past downturns -- one using futures contracts; the other a so-called long-short strategy -- the trading parameters were complex and it’s difficult to know how they’ll perform during the next downturn.

Indeed, this was the overarching theme of the study, which ultimately hedged its own conclusion:

Importantly, every crisis is different. For each crisis, some defensive strategies will turn out to be more helpful than others. Therefore diversification across a number of promising defensive strategies may be most prudent.1

Where does this leave investors worried about the next big downturn?

Ideally, it leaves them looking less at their portfolios and more to what they can control in other areas of their financial lives.

Recessions and market downturns are temporary events. With financial capacity from employment or pension income, cash reserves and spending flexibility, investors can travel the required distance to economic recovery without having to sell assets at distressed prices.

You only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out. - Warren Buffett

It can be hard to remember this when the headlines are trumpeting distressing news and a neighbor is sharing concerns. The neighbor, though, may have assumed a lot more investment risk than you or be financially overextended in other ways. Each person’s situation is different, so it’s usually best not to take your financial cues, much less advice from friends and neighbors during times of market distress.

There’s also this: stocks offer the possibility of higher returns than safer assets like cash and bonds because of all the risks to which they’re exposed, not in spite of them. If the risks go away, presumably the “equity premium” will, too, which makes stocks a lot different than the earthquakes Californians endure.

Of course, Californian’s could move elsewhere, but they’d probably find themselves exposed to other risks -- floods and tornadoes in the Midwest; hurricanes and tropical storms on the other coasts; ice storms back east, and even earthquakes these days in Oklahoma -- all of which underscores Henry David Thoreau’s observation a century and a half ago that, in the end, “[a] man sits as many risks as he runs.”